Donors

Dr. Deborah A. Abowitz ’77

Jeffrey Alexis and Christine Hay

Mr. Laurent Alpert and Ms. Johanna Fend Alpert ’64

James ’74 and Cecilia Alsina

Mr. and Mrs. Chad Anderson

Ms. Emily Andrews ’10

Ms. Sarah Andrews ’12

Anonymous (7)

Ms. Beth Bailey and Ms. Melissa McHenry

Ms. Christine Baker

Bank of America Charitable Gift Fund

Jim and Carol Barclay

Mr. Chris Becker

Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Beer

Dr. Eric L. Bell

Charlene Berry

Dr. and Mrs. Heath Boice-Pardee

Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Bowley

Mr. Christopher Brand

Ms. Whitney Brice

Mr. and Mrs. Jerry Briggs

Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Briggs

Ms. Valerie R. Bronte ’99

Mr. Ryan Brush and Mrs. Melissa Fujimoto-Brooks

Paul J. Burgo ’97

Ms. Susan Bush and Dr. Marianne Taylor

Ms. Patricia Butler

Mr. Seth Button ’97

Martha Cameron ’81

Ms. Sarah E. Chambers

Drs. Mitchell A. Chess and Patricia R. Chess

Kerry C. Cho ’88

Mr. James Chung ’89

Mr. John Clark and Dr. Nancy Shafer-Clark

Patricia Corcoran

Mr. Samuel Crabb and Dr. Glynis Scott

Mr. and Mrs. Arthur J. Dagen ’51

Mr and Mrs. William Dalton

John D’Amanda ’75 and Kathy Durfee D’Amanda ’76

Ms. MaryLynn Dandrea and Mr. Stephen Kupferschmid

Stewart D. Davis

The DeNatale Family

Sarah Dengler ’75

Beth DeWeese ’75

Mr. and Mrs. Trevor DiMarco

Mr. Michael Discenza and Dr. Jacque Trama-Discenza

Dr. Gregory Dobson

Dr. Zhiyao Duan and Ms. Yunping Shao

Mr. Nathaniel G. Duckles ’04

Robert and Lisa Duerr

Mr. Rashid Duroseau ’05

Jo Eaton and Richard Babin

Ms. Christine Edge

Dr. Charles D. Fallon ’60

Mr. Thomas E. Feldman ’76 and Ms. Andrea J. Michie

Marilyn Fain Fenster

Mr. George Ferguson and Ms. Pia Cseri-Briones

Drs. Paulo Fernandes and Lucelene Lopes

Mr. David Fetterman and Ms. Adrienne McHargue

Ms. Selena Fleming

Mr. Andrew Flinders ’89

Ms. Arline Fonda

Dr. Rich Fonda

Scott Frame ’73 and Katherine Kearns Frame ’73

Drs. Jonathan Friedberg and Laura Calvi

Mr. Lawrence Damrad Frye and Ms. Robin Damrad Frye

James and Marjorie Fulmer

Christopher Gabel ’92

Brian and Julie Gambill

John ’70 and Karen Gardner

Mr. Hugh Germanetti

Mr. Ward J. Ghory and Ms. Anne Ghory-Goodman

Richard and Joyce Gilbert

John L. Goldman ’52

Mr. and Mrs. Lee Goldman ’86

Miss Taixi Gong

Mr. Robert Gray ’92 and Ms. Alison Carling

Anthony L. and Earlene C. Gugino

Gregory and Priscilla Gumina

Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Haldeman

Haldeman Family Foundation

Cynthia Hallenbeck ’75

Ned Hallick ’68

Mr. Gregory Halpern and Ms. Ahndraya Parlato

Mr. and Mrs. Henry NG Hanson ’60

Mr. and Mrs. Chris Hartman

Barbara Hays ’47

Betsy Hecker ’73

Mr. and Mrs. Shaun Heckman

Dr. and Mrs. Wade C. Hedegard

Mr. William Hosley

Chris and Kristy Houston

Drs. Fred M. Howard and Cynthia R. Howard

Mr. Steven R. Jackson ’06

Mr. Jeremy Jamieson and Ms. Karsten Solberg

Dr. Roy Jones

Mr. and Mrs. Robert Joslyn

Ms. Elizabeth Kabes

Ms. Anna Kennedy ’13

Dr. and Mrs. Paul Kennedy

Ms. Anna J. Kieburtz ’06

Paul Kingsley and Kathleen McGrath

Ms. Naomi Kinsler

Robert Kopfman and Sharon Humiston

Dr. Harlan Kosson

Ms. Sonja B. Kreckel

Mrs. Susan Weil Kunz ’52

Ms. Marcia Layton Turner

Dr. Hochang Lee and Mrs. Christine Chung

Ms. Cynthia Lees

Ms. Hillary M. Levitt ’04

Mr. Mark Goldstein and Dr. Dena Levy

Dr. Kenneth Lindahl and Mrs. Kathy Lindahl

Dr. and Mrs. Stuart Loeb

Ms. Victoria A. Lomaglio ’06

Dr. Alan Lorenz and Ms. Nancy Sands

Dr. Frederick S. Cohn and Ms. Janice Loss

Staffan ’66 and Lee Craig Lundback ’66

Maple Ave Dental

Mr. and Mrs. Robert Marcus

Mr. and Mrs. Madhava Marri

Mrs. Kenneth Maxwell

Mr. and Mrs. Matthew McAlpin

Kurt and Lisa McConnell

Mr. and Mrs. David McCoy

Lee S. McDermott (Lee Sherwood Allen ’64)

Mr. and Mrs. Robert F. McGraw, III

Robert McLear ’88 and Claire McLear ’87

Jon and Susan Parkes McNally

Mr. and Mrs. Richard Mendolia

Dr. Mary Gail Mercurio

Mike ’78 and Betsy Merin

Jeannette C. Mitchell

Drs. Scott Mooney and Chin-Lin Ching

John ’81 and Erinne Morse

Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Mortellaro

Mr. Roderick Mortimer

Mr. and Mrs. Gary Muisus

Mr. Marvin Muller, III and Mrs. Jennifer Schwartzott

Mr. Jeffrey Neable and Ms. Laural Hartman

Mr. and Mrs. Steve Neumaier

Drs. Patricia Newcomb and Janet Gillespie

Mr. and Mrs. Franklin Nice

Carl Nielsen and Patricia Corcoran

Robert and Milena Novy-Marx

Mr. John Nugent and Ms. Dawn Thomson

Mr. and Mrs. Peter Obourn

The Oese-Siegel’s

Ms. Mirel Oese-Siegel ’08

Ms. Jean M. Oswald

Drs. Ryan-Jon Palmitesso and Alisa Kim

Mrs. Julie Walker Parker ’79

Walter Parkes

Ms. Sandra E. Patla

Mrs. Julia Messenger Pearsall ’80

Mr. and Mrs. Michael Pinch

Terry Platt and Dianne Edgar

Mr. and Mrs. Steven Plonsky

Mr. Douglas Pratt

Mr. and Mrs. David Publow

Mr. Paul Raca and Ms. Nancy Raca

Mr. Gabriel Racz ’90 and Ms. Melanie Walker

Drs. Amit Ray and Jessica Lieberman

James and Nancy Rinehart

Mr. Tim Robinson and Mrs. Page Durant Robinson ’01

Rochester Area Community Foundation

Neal Roden

Mr. and Mrs. Todd Rogers

Mr. and Mrs. David Rutberg

Jane Liesveld and Deepak Sahasrabudhe

Ms. Karen Saludo and Mr. Dennis Drew

Miss Izabella Sander

Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Sander

Sarphatie Educaton

Drs. Edward Sassaman and Michelle Shayne

Alicia Morgenberger Schober ’85

Dave and Nancy Schraver

Dr. and Mrs. Steven Schulz

Schwab Charitable Fund

Ms. Samantha R. Scott ’15

Mr. Russell Scott and Dr. Christine Scott

Mr. Amos Scully and Ms. Stephanie Ashenfelder

Chip and Marit Sheffield

Laurie Sherwood ’69

Mr. Shashi Sinha and Dr. Corinna Schlombs

The Sisson Family

Mrs. Margaret Smerbeck

Jackie Smith

Dr. Regina Smolyak

Mr. Niko Smrekar and Ms. Cara Cardinale

Alan and Helen Soanes

Drs. Alexander Solky and Valerie Lang

Dr. Hannah Solky

Mr. Paul Sparacino ’72

Mrs. Suzy Spencer

Dr. Eric Spitzer

Ms. Virginia Smythe Spofford ’74

Dr. Douglas Stockman and Ms. Marietta Cutrone

Charles Stuard ’82

Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Sullivan

Brenda Fuhrman Swain ’77

Deb and Mike Szuromi

Rustam Tahir and Vivian Lewis

Andrea Taylor

Tim Tindall and Erica Harper

Michael R. Todd ’64

Ms. Connez Todd ’65

Ted ’98 and Jennifer Townsend

Jim ’61 and Anne Townsend

Ms. Sarah Townsend ’01

Susan Turiano

Marguerite Urban and Linda Spillane

United Way of Greater Rochester

Mrs. Mary Ellen T. Urzetta

Vanguard Charitable Endowment Program

Drs. Anthony Villani and Zsuzsanna Marchl

Mr. and Mrs. Johnny Walker

Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Wallace

Mr. Andrew Washburn and Dr. Elizabeth Santos

Drs. Joseph Wedekind and Clara Kielkopf

Mr. and Mrs. William T. West

Mr. Peter V. Whitbeck ’71

Dr. Julie L. Whitbeck ’81

Bill ’58 and Bobbi Whiting

Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Wilcox

Miss Winifred S. Wilcox-Fox

Helen Wiley and Marian Payson

Mr. Alan Winchester and Dr. Larissa Temple

Mr. and Mrs. Floyd Winslow

Karen Yeoman ’98

Mr. Daniel P. Yeoman ’00 and Ms. Beth Bafford

Ms. Margot Townsend Young ’64

Dr. Xulong Zhang and Mrs. Xiaobei Qiu

Ms. Jianping Zhu

Fati Ziai ’82

Jane Hopfinger and Robert Zogas

Harley’s Approach to College Counseling

Harley’s Approach to College Counseling “Club Rush” is an afternoon every fall in the Upper School when students have the chance to sign up for clubs for the year, and each year it is very different because new clubs are created based on student initiative and enthusiasm.

“Club Rush” is an afternoon every fall in the Upper School when students have the chance to sign up for clubs for the year, and each year it is very different because new clubs are created based on student initiative and enthusiasm. Each and every year, students at The Harley School participate in HAC Athletics, and their success continues to be impressive, both as students and athletes. Our athletic program is an integral part of Harley, teaching student-athletes invaluable lessons about teamwork, time management, persistence, and competition. Our program allows them to develop physically, mentally, socially, and emotionally as they represent their school on and off the field. They grow, mature, and work hard to be the best teammate they can, while creating lifelong memories with teammates who often remain friends for life.

Each and every year, students at The Harley School participate in HAC Athletics, and their success continues to be impressive, both as students and athletes. Our athletic program is an integral part of Harley, teaching student-athletes invaluable lessons about teamwork, time management, persistence, and competition. Our program allows them to develop physically, mentally, socially, and emotionally as they represent their school on and off the field. They grow, mature, and work hard to be the best teammate they can, while creating lifelong memories with teammates who often remain friends for life.  Our Upper School is filled with formal and informal opportunities for students to take on leadership roles. Whether following passions or learning new skills, student-driven opportunities take many shapes.

Our Upper School is filled with formal and informal opportunities for students to take on leadership roles. Whether following passions or learning new skills, student-driven opportunities take many shapes. Unlike this class, death is not an elective. Although it is one of two universal human experiences, our culture often ignores, denies, or misconstrues the true nature of death and dying. What happens when we bear witness to this natural process in the cycle of life and develop our ability to be fully present with others when they need us more than ever? It has the potential to change us deeply and fundamentally while shining a brilliant light on the path of our own lives.

Unlike this class, death is not an elective. Although it is one of two universal human experiences, our culture often ignores, denies, or misconstrues the true nature of death and dying. What happens when we bear witness to this natural process in the cycle of life and develop our ability to be fully present with others when they need us more than ever? It has the potential to change us deeply and fundamentally while shining a brilliant light on the path of our own lives. This program utilizes environmentally-focused approaches to education and hands-on learning in order to foster the next generation of leaders through a lens of sustainability and problem-solving.

This program utilizes environmentally-focused approaches to education and hands-on learning in order to foster the next generation of leaders through a lens of sustainability and problem-solving. At Harley, our students learn how to evaluate social systems in order to identify complex problems in society through a lens of social justice. They take a hands-on approach to working for a fair, equitable society by researching, exploring and evaluating different perspectives, and offering solutions—both theoretical and practical.

At Harley, our students learn how to evaluate social systems in order to identify complex problems in society through a lens of social justice. They take a hands-on approach to working for a fair, equitable society by researching, exploring and evaluating different perspectives, and offering solutions—both theoretical and practical. Students may create independent studies with supervising teachers throughout their Upper School experience or, during Grade 12, they can design Capstone projects—intensive collaborations with Harley faculty and off-campus mentors—involving rigorous academic study and culminating in public presentations.

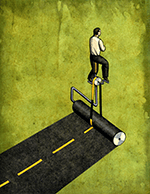

Students may create independent studies with supervising teachers throughout their Upper School experience or, during Grade 12, they can design Capstone projects—intensive collaborations with Harley faculty and off-campus mentors—involving rigorous academic study and culminating in public presentations.